SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Major corporations from oil and gas companies to retail giants would have to disclose their direct greenhouse gas emissions as well as those that come from activities like employee business travel under legislation passed Sept. 11 by California lawmakers, the most sweeping mandate of its kind in the nation.

The legislation would require thousands of public and private businesses that operate in California and make more than $1 billion annually to report their direct and indirect emissions. The goal is to increase transparency and nudge companies to evaluate how they can cut their emissions.

Companies would have to report indirect emissions including those released by transporting products and disposing waste. For example, a major retailer would have to report emissions from powering its own buildings, as well as those that come from delivering products from warehouses to stores.

“We are out of time on addressing the climate crisis,” Democratic Assemblymember Chris Ward said. “This will absolutely help us take a leap forward to be able to hold ourselves accountable.”

Huge climate win in California: Despite a massive misinformation campaign by opponents, the Assembly just passed our bill to require large corporations to be transparent about their carbon footprint.

SB 253 will make California a global leader in corporate carbon transparency.

— Senator Scott Wiener (@Scott_Wiener) September 12, 2023

The legislation was one of the highest-profile climate bills in California this year, racking up support from major companies that include Patagonia and Apple, as well as Christiana Figueres, former executive secretary of the United Nations convention behind the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

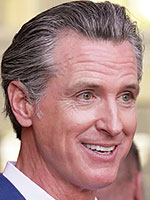

The bill would still need final approval by the state Senate before it can reach Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom. Lawmakers backing the bill say a large number of companies in the state already disclose some of their own emissions. But the bill is a controversial proposal that many other businesses and groups in the state oppose and say will be too burdensome.

Newsom

Newsom declined to share his position on the bill when asked last month. His administration’s Department of Finance opposed it in July, saying it would likely cost the state money that isn’t included in the latest budget. Newsom has advanced California’s role as a trendsetter on climate policies by transitioning the state away from gas-powered vehicles and expanding wind and solar power. By 2030, the state has set out to lower its greenhouse gas emissions by 40% below what they were in 1990.

State Sen. Scott Wiener, a San Francisco Democrat who introduced the disclosure bill, said in a statement that it would allow California to “once again lead the nation with this ambitious step to tackle the climate crisis and ensure corporate transparency.”

California has a lot of big companies that manufacture, export and sell everything from electronics to transportation equipment to food, and most every major company in the country does business in the state, which is home to about one in nine Americans. Newsom often boasts about the state’s status as one of the world’s largest economies.

The policy would require more than 5,300 companies to report their emissions, according to Ceres, a nonprofit policy group supporting the bill.

About 17 states, including California, have inventories requiring large polluters to disclose how much they emit, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. California’s climate disclosure bill would be different because of all the indirect emissions companies would have to report. Additionally, companies would have to report based on how much money they make, not how much they emit.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission proposed rules that would make public companies disclose their emissions, up and down the supply chain. But the California bill would go beyond that, by mandating that both public and private companies report their direct and indirect emissions.

Opponents of the bill say it is not feasible to accurately account for all of the mandated emissions from sources beyond what companies are directly responsible for.

“We’re dealing with information that’s either unreliable or unattainable,” said Brady Van Engelen, a policy advocate at the California Chamber of Commerce.

Way to go @envirovoters SAC TEAM! https://t.co/kBaa6e8pqn

— Aaron McCall (@MrNeuropolitan) September 12, 2023

The chamber, which advocates for businesses across the state, is leading a coalition that includes the Western States Petroleum Association, the California Hospital Association and agricultural groups, in opposing the bill. They argue many companies don’t have enough resources or expertise to accurately report emissions and say the legislation could lead to higher prices for people buying their products.

Hundreds of companies in California already have to disclose their direct emissions through the state’s cap and trade program, said Danny Cullenward, a climate economist and fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy. The decade-old program, which allows large emitters to buy allowances from the state to pollute and trade them with other companies, is one of the largest in the world.

Cullenward said the disclosure bill could lead to similar proposals in other states as federal regulators, faced with possible lawsuits in the future over disclosure mandates, “are going to be under pressure to not overreach.”

Supporters of the disclosure bill acknowledge it’s not a “perfect” solution that would guarantee flawless emissions reports. But they say it’s a starting point. California Environmental Voters, which supports the bill, says the legislation would put pressure on companies to move faster in lowering their emissions.

“Our state can’t just take 2023 off in terms of climate action,” said Mary Creasman, the group’s CEO.

The California Air Resources Board would have to approve regulations by 2025 to implement the bill’s requirements. Companies would have to begin publicly disclosing their direct emissions annually in 2026 and start annually reporting their indirect emissions starting in 2027. Companies would have to hire independent auditors to verify their reported emissions releases. The state would not penalize companies for unintentional mistakes they make in reporting a portion of their indirect emissions.

A similar proposal introduced last year passed the state Senate but failed in the Assembly. Wiener, the San Francisco Democrat who introduced the legislation both years, has said proponents of the bill built a stronger coalition this year to have a better outcome.

A key committee in the state Assembly blocked legislation earlier this year that would have sped up the state’s timeline for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Lawmakers are also weighing a bill that would require companies making more than $500 million annually to disclose how climate change could hurt them financially.