Shipping operations at Haiphong Port in Vietnam. (Linh Pham/Bloomberg)

President Donald Trump’s two-tiered trade deal with Vietnam aims squarely at practices China has long used to skirt U.S. tariffs: the widespread legal shifting of production to Southeast Asian factories and the murkier and illegal “origin washing” of exports through their ports.

The agreement slaps a 20% tariff on Vietnamese exports to the U.S. and a 40% levy on goods deemed to be transshipped through the country. With details still scarce, economists said much will hinge on the framework Washington establishes to determine what it sees as “Made in Vietnam” and what it sees as transshipments.

Complicating matters is the fact that Chinese businesses have rushed to set up shop across Southeast Asia since Trump launched his first trade war back in 2018. The lion’s share of Vietnam’s exports to the U.S. are goods like AirPods, phones or other products assembled with Chinese components in a factory in Vietnam and then shipped to America. That’s not illegal.

“A lot will depend on how the 40% tariffs are applied. If the Trump administration keeps it targeted, it should be manageable,” said Roland Rajah, lead economist at the Lowy Institute in Sydney. “If the approach is too broad and blunt, then it could be quite damaging” for China, Vietnam and for the U.S., which will have to pay higher import prices, he said.

The think tank estimates that 28% of Vietnamese exports to the U.S. were made up of Chinese content in 2022, up from 9% in 2018.

Pham Luu Hung, chief economist at SSI Securities Corp. in Hanoi, said a 40% levy on transshipped goods would have limited impact on Vietnam’s economy because they aren’t of Vietnamese origin in the first place. Rerouted exports accounted for just 16.5% of Vietnam’s shipments to the U.S. in 2021, a share that has likely declined over the past couple of years amid stronger enforcement actions by both governments, Hung said.

“An important caveat is that the rules of origin remain under negotiation,” Hung said. “In practice, these rules may have a greater impact than the tariff rates themselves.”

Devil in Details

Duncan Wrigley, chief China economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said he’s skeptical the latest deal will be effective in stamping out Chinese exports via Vietnam to the U.S.

“The devil is in the details, but I think China’s exports will either go via other markets to the U.S., or some value-added will be done in Vietnam so the product counts as made in Vietnam, rather than a transshipment,” he said.

As officials across Asia rushed to negotiate lower U.S. tariff levels with their U.S. counterparts this year, Chinese businesses have been just as quick to ramp up their exports through alternative channels in order to skirt punitive U.S. levies.

Shipments from China to Southeast Asia have reached record highs in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam this year. And there’s been a “significant increase in correlation” to the region’s increase in exports to the US during the same period, Citigroup Inc. economists said in a recent report.

Southeast Asia Trade Is Surging

Much of that is likely due to the shifting of legitimate production across the region. Goods destined for the U.S. market may be sent from their factories in Southeast Asia, and what they make in their factories in China will be sent to the rest of the world, said Derrick Kam, Asia economist at Morgan Stanley.

“If you try to represent that in the trade data, it will look exactly like rerouting, but it’s not,” Kam said. “It’s essentially the supply chain working itself out.”

Our trade deal with Vietnam is a massive win for America’s businesses, manufacturers, and farmers!

For the FIRST TIME EVER, Vietnam will open its market to the United States. They will pay 20% to sell their products here, and 40% on transshipping – meaning if another country… pic.twitter.com/lTcDsGfLx4

— Howard Lutnick (@howardlutnick) July 2, 2025

But it’s transshipment that’s been a major concern for Trump’s top trade advisers including Peter Navarro, who described Vietnam as “essentially a colony of communist China” during an April interview with Fox News.

And it’s not just been happening in Vietnam.

Not long after Trump unveiled his “Liberation Day” tariffs on April 2, garment makers in Indonesia started receiving offers from Chinese companies to be “partners in transshipment,” said Redma Gita Wirawasta, chairman of the Indonesian Filament Yarn and Fiber Producers Association.

Chinese products would be rerouted to Indonesia, undergo minimal processing like repacking or relabeling, then secure a certification that they were made in the Southeast Asian country, Wirawasta said.

When the goods are then exported to the U.S., they’d be subject to the 10% universal levy that Trump has imposed on nearly all countries, instead of the tariff for China that still equates to an effective level of over 50%, even after a recent “deal” that lowered levies from a peak of 145%.

With the huge scope for arbitrage, coupled with little policing, that process will prove tough to stamp out.

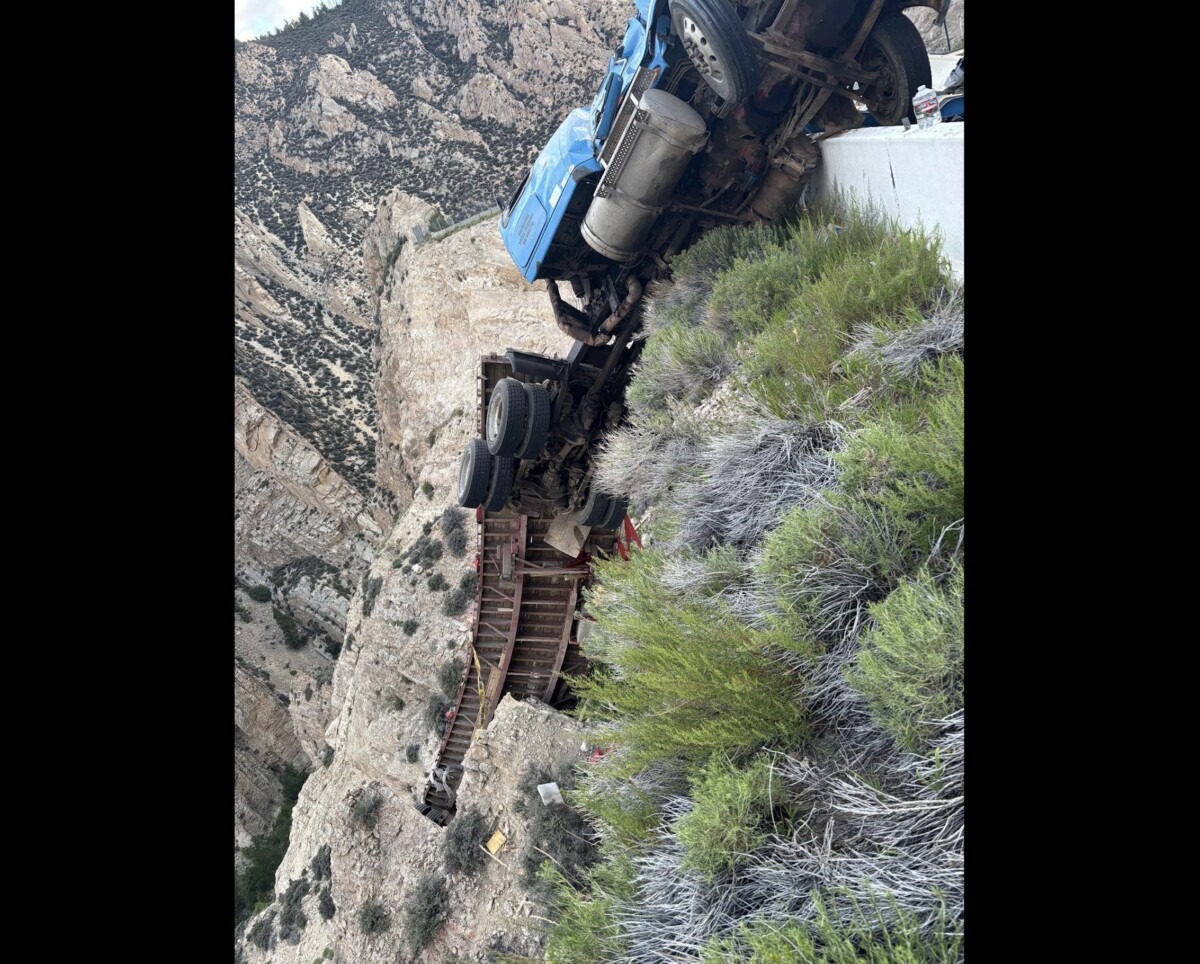

Three experts from Transport Enterprise Leasing discuss strategies for buying and selling trucks amid regulatory shifts, trade tensions and economic uncertainty. Tune in above or by going to RoadSigns.ttnews.com.

“Chinese exporters and their affiliates and partners in Southeast Asia are highly skilled at adapting to changing rules, identifying loopholes and sometimes overstating the extent of value-add by non-China countries,” said Gabriel Wildau, managing director at advisory firm Teneo Holdings in New York.

Some final assembly or transshipment may shift to rival Southeast Asian transshipment hubs like Cambodia, Thailand and Singapore, or farther afield to Turkey, Hungary or Poland, Wildau said.

“Another possibility is that the definitions and enforcement mechanisms are fuzzy, rendering the latest deal cosmetic and toothless,” he said. “Rigorous enforcement would also require a significant boost of resources to enable U.S. customs to verify compliance with the tougher rules of origin.”

There have been efforts across the region to at least be seen to be making an effort to curb the practice. Indeed, Vietnam has made a big deal about cracking down on trade fraud and illegal activity in recent months.

In April, South Korea said it seized more than $20 million worth of goods with falsified origin labels — the majority of which were destined for the U.S. The Airfreight Forwarders Association of Malaysia issued a warning in May as Chinese brokers promoted illegal rerouting services on social media.

Malaysia has centralized the issuance of certificates of origin with its Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry, while tapping its customs agency to help curb transshipment. Thailand has expanded its watch list for high-risk products, including solar panels, cars and parts, and is mulling stricter penalties for violators.

Red Tape

Casey Barnett, the president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Cambodia, is already seeing the changes in action. One factory that exports to major U.S. retailers, including Walmart, Home Depot and Lowe’s, said that customs officials were very carefully reviewing their products before being sent to the U.S., he said.

“It’s creating some additional paperwork and a little bit of red tape here,” Barnett said.

A senior manager at a logistics company in Cambodia, who asked not to be identified because the matter is sensitive, said export processing time has now stretched to as much as 14 working days — double what it was before.

But in Indonesia, getting a certificate of origin is fairly quick and painless when goods are marked for export, often just requiring a product list and a letter to the provincial trade office, according to Wirawasta. Authorities prioritize checking products that enter the country to ensure they pay the right duties and comply with regulations, he explained. It’s rare for them to inspect factories where an export good was supposedly made.

So much so that sometimes, Chinese companies don’t even need to muster up some local processing. “The T-shirt could be finished in China, with a ‘Made in Indonesia’ label already sewn on,” Wirawasta said.

“Some traders won’t even bother to unload the goods from the shipping container,” he added. “Unloading costs money.”